José Alexandre M. Demattê1, Cássio Marques Moquedace1, Eduardo Couto2, Raul R. Poppiel1, Maria de Lourdes Mendonça-Santos3, Lúcia Helena Cunha dos Anjos4, Ricardo Simão Diniz Dalmolin5, Carlos R. Espindola6, Elpídio Inácio Fernandes-Filho7, Jaime Almeida8, João Carlos Ker8, Felipe Haenel Gomes9, Luiz Toledo Barros Rizzo10

Institutional consolidation of pedology in Brazil

Pedology was established as a scientific discipline based on the pioneering work of Vasily Dokuchaev in Russia at the end of the 19th century, when he proposed that soils should be understood as natural bodies with their own genesis. This innovative approach was later expanded by Hans Jenny, especially in his work Factors of Soil Formation, published in 1941 (Jenny, 1945), which established a quantitative basis for the factors of soil formation.

In Brazil, soil science gained momentum from the 1960s onwards, with important contributions from universities, the Agronomic Institute of Campinas (IAC), and the then National Department of Agricultural Research (DNPEA), linked to the Ministry of Agriculture. With the creation of Embrapa in 1973, the DNPEA was transformed into the National Service for Soil Survey and Conservation (SNLCS), responsible for coordinating systematic soil surveys on a national scale. In 1993, this structure was reconfigured as the National Center for Soil Research (CNPS), later named Embrapa Soils, promoting the integration of field knowledge, emerging methodologies, and public policies based on scientific and technical foundations (Embrapa, 2025). This was a period of strong institutional development, marked by the standardization of procedures and advances in soil chemistry, mineralogy, and physics.

The technical consolidation of Brazilian pedology was marked by structural milestones. In 1963, the Brazilian Society of Soil Science (SBCS) published the Manual of Field Work Methods, which systematically guided the morphological description of profiles in pedological surveys. In 1977, the SNLCS organized the First International Workshop on Soil Classification, whose publication in 1978 consolidated systematic criteria for the characterization and illustration of representative profiles. These efforts culminated in the Soil Classification and Correlation Meetings (RCCs), fundamental for the construction of the Brazilian Soil Classification System (SiBCS), whose first edition was launched in 1999, with a new version published in June 2025.

For decades, Brazilian pedology played a key role in organizing knowledge about the country’s soils and in training qualified professionals, especially until the 1990s. Until then, the surveys carried out served as the basis for relevant public policies, most notably the RadamBrasil Project, aimed at the integrated mapping of the country’s natural resources. This project included the creation of maps of agricultural suitability and land capability, which are still widely used. On the other hand, between 1986 and 1992, a process of institutional dismantling began, with the discontinuation of programs such as RadamBrasil itself and the weakening of pedology in centers such as the IAC. Only units linked to soil classification remained active, such as those at Embrapa Soils and in university research groups. This context led to a period of uncertainty and a decline in the training of specialized technicians. From this inflection point, pedology has had to face the challenge of reinventing itself in the face of technological transformations, new environmental demands, and the growing social demand for more accessible, faster, and integrated soil data.

Crisis, reconfiguration, and new frontiers of pedology

After the year 2000, with the emergence of techniques grouped under the concept of Digital Soil Mapping (DSM), the SCORPAN model was consolidated (McBratney et al., 2003), a theoretical framework that expanded the foundations for predicting soil attributes and classes through algorithms and environmental covariates. However, pedology did not immediately incorporate DSM, nor did it fully assimilate emerging technologies such as high-resolution remote sensing and geostatistics. In a slower process than the adoption of aerial photography and radar in previous periods, there was resistance from technical sectors. Outside academia and graduate programs, traditional protocols continued to dominate soil surveys: definition of observation points, point sampling, conventional laboratory analyses, and personalized interpretation, with map elaboration strongly anchored in the pedologist’s experience. Although consolidated, this model presents significant limitations in terms of interpretability for users, reproducibility of results, operational costs, methodological standardization, and cartographic updating.

Paradoxically, while pedology was seeking a new path amid this shifting paradigm, society’s demand for soil information was intensifying. Emerging topics such as environmental degradation, food security, land-use planning, and the implications of climate change began to require faster, broader, and more transparent responses, which traditional methods could not deliver with the same agility. This lag increased the perception that pedology was being left behind.

Almost simultaneously, there was a decline in the training of new pedologists. As early as 2002, SBCS bulletins raised the provocative question: had pedology “died”? This critical phase created a structural gap between the growing demand for soil data and the installed capacity to produce them—both in scale and analytical diversity.

Another central issue concerns the way pedological maps are presented and interpreted by society. To this day, these maps are not easily understood, which leads to resistance to their use, despite their unquestionable wealth of information. There is, therefore, a mismatch between the data provided by pedological maps and the information users actually need for their daily decisions. For example, the importance of texture and mineralogy in the dynamics of water and solutes in the soil is widely recognized, with direct impacts on plants and agricultural productivity. This is well-established knowledge, the result of decades of research, with international recognition of Brazil’s contribution to the study of tropical soils. However, to what extent has this knowledge been effectively translated into accessible information for farmers? Is it applied, for instance, in fertilizer recommendations and fertility management based on these attributes—or even more remotely, based simply on soil classification?

In general, soil attributes and types are still used empirically, not quantitatively, often by actors who possess valuable local knowledge that must not be neglected or lost. It is necessary to recover this knowledge—both traditional and scientific—and place it at the service of society. After all, what scientific project today does not require a connection between its final product and the community? In this context, artificial intelligence (AI) may offer promising solutions to this challenge of translating and applying pedological knowledge.

Precision agriculture, for example, has managed to integrate knowledge of soil fertility with Geographic Information System (GIS) tools, linking soil properties to georeferencing to optimize agricultural management. One could say that the field of soil fertility “did its homework” and managed to establish a more direct line of communication with users. On the other hand, there are still few studies that relate pedological maps to production environments, management zones, planting and harvesting times, productivity, land selection, and conservation planning, such as in the case of ZARC (Climate Risk Zoning). Nor are there integrated approaches that combine mineralogy, fertilization, irrigation planning, soil surface temperature, and climate impacts. In light of the advancement of geotechnologies, pedology now has the opportunity to significantly expand its interface with society—just as it did in its early days. In this scenario, AI emerges not as a rupture with the past, but as a coherent development of its scientific trajectory. AI appears as a natural evolution, capable of amplifying the analytical capacity of the discipline and strengthening its interface with practice.

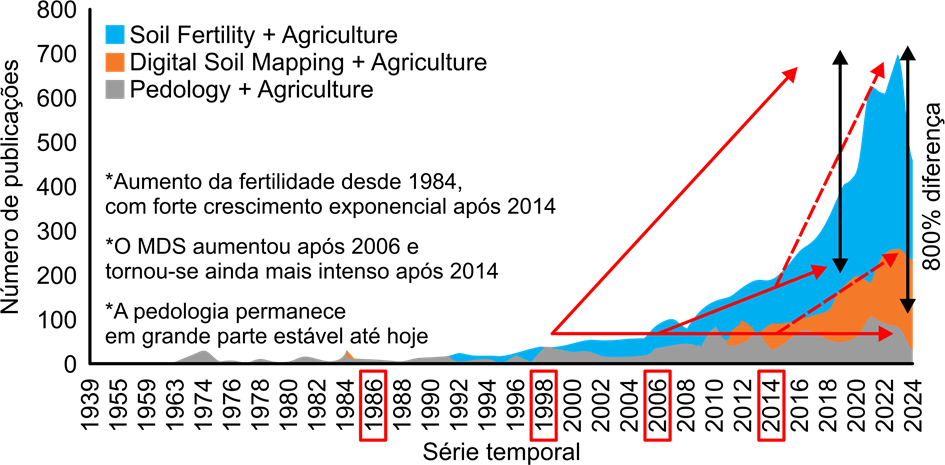

Thus, pedology finds itself at a moment of paradigmatic change, in which it can integrate decades of accumulated knowledge with advanced computational tools, maintaining its scientific essence while exponentially expanding its capacity to contribute to society. Soil data provide technical information that enables inferences about spatial variability, as well as supporting new solutions in agro-environmental contexts. Pedological maps at more detailed scales allow the observation of intrinsic soil attribute distributions that directly affect crop performance and ecosystem resilience. However, this perspective has been little explored throughout the history of Brazilian pedology (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Evolution in the number of scientific publications relating Agriculture to three different approaches in Soil Science: Soil Fertility (blue), Digital Soil Mapping (orange), and Pedology (gray), from 1939 to 2024. Source: Modified from Demattê et al. (2025).

There is a notable mismatch between the production of pedological knowledge and its transfer to society, particularly when compared to the field of soil fertility. The latter has understood social demands and remained ahead of them, establishing itself as a leading technical reference. Evidence of this is that scientific publications with the terms fertility + agriculture have surpassed those with pedology + agriculture by up to 700% in recent years (Figure 1). This gap goes beyond the quantity of publications—it also reveals the science’s ability (or lack thereof) to engage in meaningful dialogue with the needs of the field.

On the other hand, it is interesting to note that the arrival of pedometrics in the Brazilian context, starting in 2002, marks a turning point. From 2014 onwards, there has been a significant increase in publications involving digital soil mapping (DSM) and agriculture, precisely during the period when the adoption of geotechnologies and predictive algorithms intensified. Figure 1 highlights this leap, indicating that the incorporation of quantitative approaches has been serving as a driver of renewal in pedology, once again bringing it closer to contemporary challenges in agriculture and environmental sustainability.

Digital Transformations in Pedology: The Strategic Role of Artificial Intelligence

The incorporation of artificial intelligence (AI) in pedology represents a paradigmatic shift that goes beyond mere technological modernization. The holistic view of soil, which considers form, function, genesis, and landscape, becomes even more relevant in the face of demand for sustainable, integrated, and data-driven solutions. AI tools have begun to process large volumes of information, identify complex patterns, and propose inferences about genesis, horizon differentiation, morphological groupings, and even spatial patterns that are hardly perceptible to the human eye.

These innovations promote a significant acceleration of analyses, reduction of subjectivity, such as in the reading of soil color and structure (Gómez-Robledo et al., 2013; Han et al., 2016; Mancini et al., 2020; Stiglitz et al., 2016), and a greater capacity to integrate multiple data sources, such as satellite images, proximal sensors, digital elevation models, climatic data, and field observations. This results in more robust and comprehensive decision systems. None of these assumptions, however, replace field excursions, which remain indispensable for direct observation, sample collection, and validation of predictions.

Machine learning algorithms, and more recently deep learning, are able to identify subtle spectral patterns that correspond to specific chemical properties. Convolutional neural networks already analyze micromorphology images with precision superior to human visual interpretation. Other algorithms integrate proximal sensor data, orbital images, and climatic time series to predict soil properties at the landscape scale. This advance expands pedology’s analytical capacity in understanding and modeling edaphic systems.

Methodologically, this new pedological context can be synthesized by a fundamental logical chain: sensor → model → estimated property. It is an inferential flow in which data generated by sensors (reflectance, relief, climate, etc.) are processed by machine learning algorithms, which in turn produce estimates of soil attributes such as texture, organic carbon, color, or taxonomic class. This structure, although technologically sophisticated, requires the same principles of good science: sampling rigor, statistical validation, and above all, pedological interpretation.

The effectiveness of models therefore depends both on data quality and on the judgment capacity of the professionals involved. The models also allow quantifying uncertainties associated with conventional mappings, in which the human factor, while essential, often carries biased perceptions. Thus, the models represent a significant advancement over traditional mapping, enabling more reliable, informative maps that can be continuously updated in light of new information or computational advances.

Beyond attribute prediction, AI has already been applied in the delimitation of management zones, prediction of taxonomic classes, detection of outliers in soil databases, and uncertainty-guided sampling planning, with promising results. Such applications reinforce its usefulness not only as an analysis tool but as an active element in the agro-environmental decision-making process.

Finally, it is important to recognize that the use of AI in pedology also poses new epistemological challenges. It requires solid technical training, mastery of statistics and programming, but above all, the maintenance of pedological logic as the core for interpreting results. There are also relevant methodological limitations: models trained with localized data tend to fail in broad geographic extrapolations, and poorly calibrated algorithms can reinforce the very biases they seek to overcome. In other words, AI does not replace the pedologist but exponentially expands their reach, provided it is well guided and interpreted. AI does not substitute field excursions, which remain irreplaceable to fully reveal soil variability and anchor interpretations in direct observations of the landscape.

Critical Risks and Challenges

The main risk of applying artificial intelligence to pedology does not lie in the technology itself, but in the uncritical use of its results. When automated models are taken as absolute truths, without mediation by pedological judgment, there is a risk of standardizing the landscape, ignoring morphological singularities, and making decisions based solely on what is easiest to measure or model, and not necessarily what is most relevant from a pedological point of view. Hence the importance of having a professional with a solid understanding of the relationships between soil-forming factors and their expression in the field.

Furthermore, just as in traditional pedology, the very logic of AI can induce methodological biases. What is considered “relevant data” tends to be defined by digital availability, not by scientific representativeness. This becomes especially critical in poorly sampled regions or areas lacking legacy data. On the other hand, the subjectivity inherent in human interpretation, without the support of available technologies—which are often more objective and replicable—can also generate judgments of high variability, as occurs in attributes sensitive to perception, such as soil color, historically determined by direct visual observation.

A classic study by Campos & Demattê (2004) revealed that four experienced pedologists, when analyzing the same samples, arrived at divergent classifications. The differences were not only due to interpretative criteria but also physiological factors, such as the age of the optic nerves, which affect visual perception of color. This example highlights the degree of subjectivity involved, even among specialists, and reinforces the role of optical sensors as allies in the quest for greater objectivity, provided they are accompanied by contextual interpretation. This challenge is even more relevant in Brazil, where the Brazilian Soil Classification System (SiBCS) adopts color as a central criterion of taxonomic distinction at hierarchical levels such as suborder and, indirectly, even at the order level, as in the definition of the A chernozemic horizon. Thus, color, although accessible and historically useful, also carries a subjective load that needs to be technically qualified, especially in view of contemporary demands for standardization and traceability.

Another study well illustrates the tension between technical judgment and digital tools. In Bazaglia Filho et al. (2013), five experienced pedologists produced a pedological map of the same area with access to the same tools, resulting in maps with degrees of variation, although coherent with each other. However, when a single pedologist produced a new map for the same area, now with intensive support from geotechnologies and digital data but maintaining pedological judgment as the final instance, the accuracy of validation increased considerably.

This is a striking example of how new technologies, far from replacing the pedologist and the field, expand their interpretative capacity and reduce a significant part of subjectivity. More than automating, it is about enhancing technical decision-making based on data and models, but without relinquishing the pedological logic that sustains soil knowledge as a natural body.

Although traditional pedological maps represent an invaluable technical and scientific heritage, it must be recognized that historically they have lacked formal metrics of accuracy or uncertainty, both at global and spatial scales. Associations between soil classes and mapping units were, as a rule, based on the pedologist’s experience and judgment, which, although valuable, is fundamentally subjective and rarely quantitatively validated. In general, the uncertainty of these associations was never estimated nor communicated to the end user.

With pedometry, the possibility opens up to quantify the degree of confidence in estimates, using tools such as prediction intervals, confidence bands, or more recent methods like conformal prediction (Balasubramanian et al., 2014; Kakhani et al., 2024) or the area of applicability of maps (AOA) (Meyer & Pebesma, 2021). These resources allow informing, point by point, where the model is more reliable and where caution is needed, promoting greater transparency and usefulness of the products generated. This advance represents not a rupture with tradition but an essential methodological complement to make pedological maps more robust, auditable, and compliant with current demands of territorial planning, environmental monitoring, and resource governance.

However, excessive dependence on digital data can create significant methodological vulnerabilities. Transparency in inference processes requires more than accuracy: it demands the explicit incorporation of uncertainty metrics. Maps that indicate not only what is estimated but with what degree of confidence are fundamental for prudent decisions in territorial, agricultural, or environmental planning.

In the Brazilian context, marked by extreme pedological diversity and strong inequality in the spatial distribution of data, there is the risk of building models that perform robustly in some regions but fail critically in others. Therefore, there is broad scope for research and development of methodologies adapted to tropical conditions, just as occurred with the creation and evolution of SiBCS. Artificial intelligence, in this sense, can accelerate responses and point to pathways for more consistent models, provided it is guided by solid technical criteria sensitive to context.

The history of pedology shows that its strength lies precisely in the ability to incorporate technical innovations without giving up critical analysis. No transition—from fieldwork to aerial photogrammetry, from topographic charts to digital maps, or from the use of radar images—has replaced the pedologist as interpreter of soil distribution in the landscape, nor the fieldwork as an essential stage for the execution and validation of mappings.

This mediating role is longstanding. A striking example is found in the SNLCS manual (Embrapa, 1988), which guided the conversion of organic carbon stocks estimated by its guidelines to values compatible with the Soil Conservation Service (SCS), using the factor 1.724, the inverse of 0.58, as a correction coefficient. Such adjustment was not merely mathematical: it demanded technical judgment about data origin, its method of obtaining, and the purpose of use. With artificial intelligence, the principle remains: it must amplify the pedologist’s role, never replace it.

Epistemological Critiques and Conceptual Challenges

The integration of artificial intelligence into pedology raises fundamental epistemological questions about the nature of scientific knowledge of the soil. As in any field with established practices, it is natural for technological approaches to encounter resistance. This skepticism, when well-founded, is healthy: it forces the new to prove itself useful and technically robust. The problem arises when this resistance is driven by ignorance or blind attachment to tradition. For example, some still do not know about the possibility of visualizing satellite images in 3D, a resource already trivial in various software. Denying this or disqualifying a digital pedological map without indicating the data source or knowing the methodology applied is, at best, a conceptual error and does nothing to advance scientific debate.

The automatic rejection of new tools simply because they represent change is untenable. Distinct techniques, applied at different scales, data sets, and purposes, can generate diverse representations of soil, all scientifically valid. Ignoring this is confusing technical rigor with rigidity. Traditionalism, when it refuses to admit the legitimacy of well-founded alternative methods, ceases to be prudence and becomes an obstacle.

This conflict is clearly expressed in automated soil classification. Machine learning algorithms categorize profiles based on large volumes of spectral, morphological, and legacy data. However, they operate by statistical correlations, not by understanding pedogenetic processes. This means that a classification can be statistically correct and pedologically mistaken, especially when immeasurable factors—such as landscape history, abrupt transitions, or specific processes—are fundamental. The illusion of algorithmic objectivity can thus mask incorrect interpretations.

The discussion goes beyond technique. It touches the epistemological core of pedology. Soil science has always relied on the articulation between systematic observation, theoretical knowledge, and contextual interpretation. This process, often accused of being “subjective,” constitutes an advanced form of analysis, based on accumulated experience and sensitive to the complexity of natural environments. Digital modeling, rather than suppressing this knowledge, should benefit from it. But for that, pedological knowledge must not be treated as passive heritage but as a fundamental interpretative asset.

Deep learning models, by revealing hidden patterns among spectra, environmental variables, and soil attributes, have suggested groupings that do not coincide with SiBCS classes. In other cases, they infer pedogenetic processes not previously described, based on integrated covariate modeling. AI, in this sense, goes beyond applying knowledge: it suggests hypotheses, anticipates questions, challenges paradigms. This should not be feared but understood. It is an invitation to dialogue between different ways of producing science, not a substitution.

If pedology wants to maintain its relevance, it must embrace this challenge with critical spirit and openness. The knowledge accumulated by pedologists—about genesis, morphology, spatial patterns, and nonlinear transitions—can be essential in various stages of modeling: variable selection, construction of interpreted layers, rule-based systems (RBS), and contextual map validation. Ignoring this knowledge cedes space to automated heuristics which, although efficient, often operate without any notion of the processes that truly form soil.

The greatest risk lies in the training of new generations. If curricula prioritize only computational skills at the expense of field experience and conceptual reflection, a worrying rupture may occur between technological innovation and pedological knowledge. AI, no matter how advanced, will continue to depend on critical human analysis to validate, interpret, and contextualize its results.

The solution is neither to reject technology nor to conserve old methods out of nostalgia. The challenge is to build a hybrid science where empirical, theoretical, and computational knowledge meet complementarily. Algorithmic precision should not erase field experience. On the contrary, it should enhance it. Only then will pedology continue to be a science capable of explaining soil, not merely describing it by correlation.

Integration Perspective

Today, there is a multiplicity of sensors, mathematical methods, and artificial intelligence algorithms that expand possibilities for acquiring, analyzing, and interpreting soil data. These sensors can be in the field or the laboratory, in the hands of pedologists, mounted on drones, airplanes, or satellites, providing rapid and massive information about soil type, location, and even indirect analyses of its attributes. It is fundamental, however, to reinforce that such techniques require field verification, standardization, and validation, the latter still being the best way to understand pedological reality. Digital techniques, when coupled with AI, allow the study of soil at multiple scales—from local detail to regional mapping—always according to the study’s objectives and questions.

Moreover, AI can integrate professionals from different disciplines. As a transversal technology, it enables the analysis of the same concept from data and methods originating from diverse fields. This connection is evident, for example, in the study of soil reflectance and its relationship with present minerals, physicochemical properties, and biological processes that directly affect the carbon cycle and, on a larger scale, climate. Surface temperature, measured by remote sensors, is also strongly related to land use and management, mineralogy, and structure. This chain of reasoning intertwines pedology, remote sensing, microbiology, soil physics, ecology, and climatology. These relationships would hardly emerge from isolated or purely empirical approaches. AI has the potential to anticipate these interactions, reveal hidden patterns, and provide initial guidelines for investigation. But it is the human who interprets, formulates hypotheses, and decides the path. Creativity and the capacity to understand exceptions remain irreplaceable. AI can suggest routes; the pedologist charts the course.

In this sense, initiatives like PronaSolos represent a promising institutional shift aimed at the systematic organization of soil data at the national scale. However, to fulfill their potential, they need to be inserted into a broader digital ecosystem, interoperable and connected with international initiatives such as SoilGrids (Hengl et al., 2017; Poggio et al., 2021), the LUCAS Soil in the European Union, or the emerging SoilPrint concept (Gobezie & Biswas, 2024), which proposes mechanisms for traceability and cryptographic authentication of pedological data. The advance of digital pedology depends not only on the quantity and quality of data but also on an institutional infrastructure that organizes, documents, shares, and protects it. This includes open formats, standardized metadata, and ethical guidelines for the use of sensitive information, such as data on private properties or indigenous lands. Without such governance, both the scientific reliability of the generated products and their social legitimacy are compromised.

In this scenario, Brazil already shows significant advances. A notable example is SoilData, a public repository developed by MapBiomas in partnership with the Pedometrics Laboratory of the Federal Technological University of Paraná, largely fed by the FEBR project (Brazilian Free Repository for Soil Data). This initiative gathers and harmonizes thousands of physicochemical soil analyses, currently with more than 11,000 texture points and 12,500 organic carbon points, all georeferenced, standardized, and available in open format. These data directly feed the products of the MapBiomas Solo platform, such as the annual carbon maps from 1985 to 2023 and static granulometric property maps. This is a concrete example of open science applied to pedology: with version control, traceability, transparent licensing (CC-BY), and integration with international standards like Dataverse. SoilData is not just a robust technical database; it is a model of public governance of soil data, with the potential to become an institutional reference in the country and a direct dialogue channel with global initiatives.

A similar example is the Brazilian Soil Spectral Library (BESB), which currently gathers over 50,000 spectral samples donated by 81 collaborators from 69 institutions, covering all 26 Brazilian states and the Federal District. It is the largest public spectral library in the world, composed of data in the visible, near-infrared, and shortwave infrared ranges (VIS-NIR-SWIR), also in the mid-infrared range (Mid-IR). This spectral breadth, combined with the represented pedoclimatic diversity, provides a unique base for training machine learning models aimed at predicting pedological attributes, expanding the applicability of spectroscopy on regional and national scales. More than a technical repository, BESB reflects a collective effort of collaborative science, integrating data from research institutions, universities, and public agencies. In synergy with SoilData, it constitutes a foundation for national pedometry and an essential starting point for structuring initiatives that seek to consolidate digital soil science in the country.

In 2025, another important institutional advance was the approval of the first National Institute of Science and Technology (INCT) dedicated to soils, the INCT Soils of Brazil, focused on characterization and modeling of pedological attributes at multiple scales. The project articulates laboratories and universities from different regions, promoting methodological innovation and training qualified personnel. Its scope includes the use of spectroscopy, digital mapping, machine learning, and integration with international networks, directly aligning the Brazilian scientific agenda with the reflections discussed in this work. It represents a concrete opportunity to operationalize digital pedology based on high-quality data, harmonized protocols, and articulation between tradition and technology.

A particularly promising development of digital pedology is technological mobility, enabled by advances in sensors on mobile devices and so-called TinyML—machine learning embedded in low-power microcontrollers. Technologies that were once restricted to laboratories or dedicated servers now reach the field, operating in real time and at accessible costs. Mobile applications capable of capturing spectra, interpreting profile images, or estimating attributes based on pre-trained models are in development and can radically transform rural extension, participatory monitoring, and citizen data collection. This decentralization expands the reach of digital pedology beyond research centers, making it a concrete tool for farmers, field technicians, schools, and communities. Connectivity, interoperability, and citizen science begin to walk together.

As this new pedology takes shape, data governance becomes a central ethical challenge. The collection, modeling, and dissemination of soil information involve sensitive issues: ownership, consent, territoriality, and access. It is urgent that Brazil discuss the concept of the “right to pedological data,” recognizing soil as a common good but with locally specific uses and contexts. There even arises the notion of spectral privacy—the right of farmers, traditional communities, or indigenous peoples to control inferences about their soils from public data, especially spectral data. In many cases, soil is inferred, mapped, and interpreted without any consultation with local populations. This demands participatory governance mechanisms, algorithm traceability, transparency in inferences, and clear guidelines on anonymization and licensing. Without these safeguards, there is a risk of building a powerful technoscientific infrastructure that is indifferent to principles of territorial justice, sovereignty, and equity.

Conclusion: A Call for Integrated Education

Artificial intelligence does not replace human intelligence; it depends on it. It can process data but does not understand landscapes. It can identify patterns but does not formulate relevant questions. It can learn from millions of observations but does not interpret processes nor judge contexts. The real challenge, therefore, is not technological but educational.

We need to prepare pedologists capable of dialoguing with algorithms without abandoning pedological thinking. Professionals who master both the field and the code. Who know how to read the soil with both the pedological knife and the pixel. Persisting in traditional practices merely to maintain the status quo, ignoring today’s available technologies, is negligence. But blindly following what the machine suggests, without critical reading or pedological understanding, is flirting with naivety or bad faith.

The challenge lies in training pedologists literate in AI and data scientists literate in pedology. Only then will it be possible to ensure that soils continue to be understood in their complexity, with technical rigor, interpretative sensitivity, and commitment to the territory. AI should be seen as a powerful but delicate tool in its application: in well-trained hands, it broadens vision, reveals hidden relationships, and strengthens pedological science. Like any tool, it depends on the training of its operator.

The future of pedology is not about choosing between tradition or innovation but about training professionals who master both. This includes investing in national programs directly connected to the population’s needs, with accessible language and focus on applicability. As has been said: “a soil map may be beautiful, but if it hangs on the wall, it will serve no purpose.” The creation and funding of initiatives that dialogue with social demands are fundamental, since knowledge about soils directly impacts agriculture, climate, conservation, and territorial planning.

The creation of PronaSolos had this purpose: to create demand and transform pedological knowledge into public policy. However, its progress has been limited, largely due to lack of funding for detailed-scale surveys essential for decision-making. Currently, only about 5% of the national territory has mapping at scales equal to or greater than 1:100,000. Meanwhile, the evolution of the SiBCS and specific projects, such as those by FINEP and CNPq, have contributed to standardizing protocols and methodologies.

In personnel training, the UNISOLOS Network (https://unisolos.ufrrj.br/) stands out, composed of four universities with solid experience in soils and geoprocessing: UFRRJ, UFMG, UFV, and UFRA. This network offered the first specialization course in Geoprocessing, Soil Survey, and Interpretation, in a distance-learning mode, through the CAPES/UAB system—a strategic initiative to expand the reach and technical qualification nationwide.

The Radam Project was a milestone in its time. Why not now advance a new joint endeavor that unites tradition and technology, field and algorithm? Soil science must be at society’s service, understanding its needs and delivering useful, clear, and applicable knowledge.

In 2025, after more than three decades of advances in artificial intelligence, the transformative impact of these technologies on pedology can no longer be ignored. Perhaps it is time to recognize that today’s soil science is not merely a modern version of the traditional discipline, nor a complete rupture. It is a science in motion, which has historically always incorporated the best available ideas, tools, and concepts. AI is not its end but its new chapter.

Final Considerations

This reflection aims to contribute to a necessary and urgent debate within the Brazilian pedological community. Technological transformation is already underway, and it is up to soil professionals to guide it with critical thinking, responsibility, and strategic vision. The pedology of the future will be one capable of integrating innovation and tradition, expanding its analytical tools without abandoning its conceptual foundations and commitment to the territory.

The challenge for this generation is to train pedologists and pedometrists who act as guardians of accumulated knowledge but also as protagonists in building pedology integrated with digital techniques. Professionals prepared to operate between field and code, between profile and algorithm, capable of dialoguing with different areas of knowledge, from geoinformation to microbiology, from ecology to data science, with technical mastery and a critical stance.

This new pedology, anchored in pedometry, must assume its strategic role in Brazilian society: contributing reliable diagnostics, supporting well-founded public policies, subsidizing territorial planning actions, and promoting environmental governance. But it also needs to be ethical, transparent, and sovereign in its use of technologies and the data it handles.

The future of pedology is not about choosing between tradition or innovation but about cultivating professionals who know how to combine both with intelligence, awareness, and public purpose.

About the authors: ¹University of São Paulo (USP) | “Luiz de Queiroz” College of Agriculture (ESALQ) | GEOCiS – Group of Geotechnologies in Soil Science – Pedology and Geotechnologies; ²Federal University of Mato Grosso (UFMT) – Pedology; ³EMBRAPA Soils | Rio de Janeiro, RJ – Pedometrics; ⁴Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ) | Institute of Agronomy, Department of Soils, Seropédica, RJ – Pedology; ⁵Federal University of Santa Maria (UFSM) | GEPED – Study Group on Pedology and Pedometrics; ⁶University of São Paulo (USP) | Department of Geography; São Paulo State University (UNESP), Rio Claro; State University of Campinas (UNICAMP), Faculty of Agricultural Engineering and Institute of Geosciences, Pedology and Geomorphology; ⁷Federal University of Viçosa (UFV) | Laboratory of Pedometrics and Geoprocessing (LabGeo) – Pedometrics and Geoprocessing; ⁸Federal University of Viçosa (UFV) – Pedology; ⁹Federal University of Lavras (UFLA), School of Agricultural Sciences of Lavras (ESAL) – Pedology; ¹⁰Agronomist Engineer – Pedology.

References

Balasubramanian, V., Ho, S. S., & Vovk, V. (2014). Conformal Prediction for Reliable Machine Learning: Theory, Adaptations and Applications. In Conformal Prediction for Reliable Machine Learning: Theory, Adaptations and Applications. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2012-0-00234-7

Bazaglia Filho, O., Rizzo, R., Lepsch, I. F., do Prado, H., Gomes, F. H., Mazza, J. A., & Demattê, J. A. M. (2013). Comparação entre mapas de solos detalhados obtidos pelos métodos convencional e digital em uma área de geologia complexa. Revista Brasileira de Ciencia Do Solo, 37(5), 1136–1148. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-06832013000500003

Campos, R. C., & Demattê, J. A. M. (2004). Soil color: Approach to a conventional assessment method in comparison to an automatization process for soil classification. Revista Brasileira de Ciencia Do Solo, 28(5), 853–863. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0100-06832004000500008

Embrapa. (1988). Definição e notação de horizontes e camadas do solo. https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/bitstream/doc/338493/1/SNLCS-DOC-3-1988.pdf

Embrapa. (2025). Embrapa Solos – Portal Embrapa. https://www.embrapa.br/solos

Gobezie, T. B., & Biswas, A. (2024). Preserving soil data privacy with SoilPrint: A unique soil identification system for soil data sharing. Geoderma, 442, 116795. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GEODERMA.2024.116795

Gómez-Robledo, L., López-Ruiz, N., Melgosa, M., Palma, A. J., Capitán-Vallvey, L. F., & Sánchez-Marañón, M. (2013). Using the mobile phone as munsell soil-colour sensor: An experiment under controlled illumination conditions. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 99, 200–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2013.10.002

Han, P., Dong, D., Zhao, X., Jiao, L., & Lang, Y. (2016). A smartphone-based soil color sensor: For soil type classification. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 123, 232–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2016.02.024

Hengl, T., De Jesus, J. M., Heuvelink, G. B. M., Gonzalez, M. R., Kilibarda, M., Blagotić, A., Shangguan, W., Wright, M. N., Geng, X., Bauer-Marschallinger, B., Guevara, M. A., Vargas, R., MacMillan, R. A., Batjes, N. H., Leenaars, J. G. B., Ribeiro, E., Wheeler, I., Mantel, S., & Kempen, B. (2017). SoilGrids250m: Global gridded soil information based on machine learning. PLoS ONE, 12(2), e0169748. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169748

Jenny, H. (1945). Factors of Soil Formation: A System of Quantitative Pedology. Geographical Review, 35(2), 336. https://doi.org/10.2307/211491

Kakhani, N., Alamdar, S., Kebonye, N. M., Amani, M., & Scholten, T. (2024). Uncertainty Quantification of Soil Organic Carbon Estimation from Remote Sensing Data with Conformal Prediction. Remote Sensing 2024, Vol. 16, Page 438, 16(3), 438. https://doi.org/10.3390/RS16030438

Mancini, M., Weindorf, D. C., Monteiro, M. E. C., de Faria, Á. J. G., dos Santos Teixeira, A. F., de Lima, W., de Lima, F. R. D., Dijair, T. S. B., Marques, F. D. A., Ribeiro, D., Silva, S. H. G., Chakraborty, S., & Curi, N. (2020). From sensor data to Munsell color system: Machine learning algorithm applied to tropical soil color classification via NixTM Pro sensor. Geoderma, 375, 114471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2020.114471

McBratney, A. B., Mendonça Santos, M. L., & Minasny, B. (2003). On digital soil mapping. Geoderma, 117(1–2), 3–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7061(03)00223-4

Meyer, H., & Pebesma, E. (2021). Predicting into unknown space? Estimating the area of applicability of spatial prediction models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 12(9), 1620–1633. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13650

Poggio, L., De Sousa, L. M., Batjes, N. H., Heuvelink, G. B. M., Kempen, B., Ribeiro, E., & Rossiter, D. (2021). SoilGrids 2.0: Producing soil information for the globe with quantified spatial uncertainty. Soil, 7(1), 217–240. https://doi.org/10.5194/soil-7-217-2021

Stiglitz, R., Mikhailova, E., Post, C., Schlautman, M., & Sharp, J. (2016). Evaluation of an inexpensive sensor to measure soil color. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 121, 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2015.11.014